[SPOILERS ALERT]

Content warning: rape, mental illness, graphic content

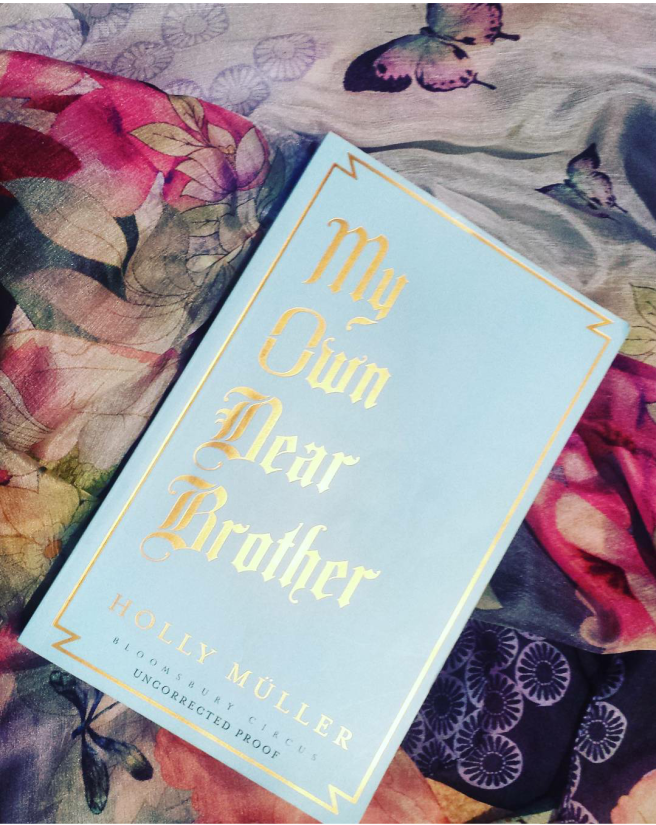

I got the proof copy of this book at Cheltenham Literature Festival where I worked in October. I knew instantly that it was a book I’d be interested in; a coming-of-age type story with a historical setting. The book is set in Austria during World War II, a period of history that I studied for A-levels.

Müller is half-Austrian and it seems like she’s really done her research. The knowledge is discreet but well implemented. While the book isn’t directly focusing on the war, it definitely looks at the impact on normal, rural folk trapped in the midst of it all – and the horrendous consequences of that.

Because what surprised me most about this book was the grisly shock factor of some of the horrendous things that these normal people suffered. Everyone knows the atrocities of WWII, the Concentration Camps, mass genocide, discrimination and persecution. But this story performs like a microcosm for for the macro experience of the war in the cities and globally. The social discrimination in these rural villages, the fear of war and the families torn apart by its losses, but also the exploitation of these rural folk trying to live a quiet life with a POW camp on their front door step. It shows the superiority complex of the countries leaders which filters down through the ranks of their armed forces who believed they were entitled to what they wanted because of the badge they wore.

Certainly the rape and exploitation of a barely teenage girl and other girls and women in the town of Felddorf was an aspect I wasn’t expecting when I started reading. The descriptions are even more harrowing as they are described from the naive and unknowing point go view of Ursula, not even 13 years old at the start of the book. Her naivety and youth, as well as her unprejudiced and undiscriminating voice is refreshing throughout most of the book, such as her friendship with Schosi. While Schosi is shunned by most people in the village, including Ursula’s own brother, for his mental disabilities, Ursula embraces him as her friend and enjoys his company for who he is. It’s not that she is anti-discrimination, more that she is so young and uninfluenced by social prejudice that she is undiscriminatory, she doesn’t consider that Schosi’s differences are in any way a reason to treat him differently.

In this way, Ursula reminds me of Scout in To Kill a Mockingbird. She is unprejudiced in her youth and doesn’t see the colour of people’s skin when she looks at them, only their quality as a person, much like Ursula. While this is a refreshing form of narration and gives Ursula a lot of her charm in her similarly Scout-like tom-boyish ways, it also makes her naive to the toxic relationship with her brother and what his anger and blood-thirst represents in a world war.

In her unprejudiced point of view throughout the book, Ursula simply does what she thinks is right and ultimately this teaches her right from wrong. Initially her blind worship of her brother makes her believe what he says is right, ruining her mother’s first positive relationship and shunning Schosi. As the true nature of her brother’s personality is slowly revealed (we learn of his exploitative and abusive actions even before Ursula understands what he has done to her), Ursula begins to learn that family doesn’t always mean protection. She goes against her brother and mother’s orders to stay away from Schosi, going with Herr Esterbauer to rescue him from an asylum; trying to right the wrongs her brother convinced her were right.

While the horrors of the war filter into the already difficult growing-up of Ursula, there are descriptions of folklore, myths, legends and landscapes that are as vividly visceral to the reader as they are in Ursula’s imagination. The lighthearted dances in the Gasthaus and playing by the river contrasted with them being forced to carry bodies into mass graves, and the loaded implications of Ursula and her sister having to drink mint tea four times daily after the Russian soldiers have forced themselves onto the girls and into their lives.

Whilst it is not an easy read, it is so for all the right reasons. MY Own Dear Brother is unforgiving but completely captivating and well worth reading.